@fantaghiro

2017-03-27T03:40:08.000000Z

字数 21341

阅读 7654

B2U5T1 The Myth of the Renaissance in Europe

文本细读 商务英语综合教程

The idea that man simply "re-found" himself during the European Renaissance ignores something quite fundamental. Jeremy Brotton argues that important developments in trade and science, as well as contact with far-flung empires, were the real causes of this seismic cultural shift.

The idea that man simply "re-found" himself during the European Renaissance ignores something quite fundamental.

- 认为人们在欧洲文艺复兴期间只是“重新找回了”自己,这种想法忽略了某些颇为根本的/重要的东西。

- 本文其实一直旨在还原文艺复兴的真实面貌。作者认为将文艺复兴简单定义为“重新发现自己”,太过简单了,无法覆盖文艺复兴的全部意义。在本句的后面一句就讲到了作者认为这样简单的定义忽略了什么。

Jeremy Brotton argues that important developments in trade and science, as well as contact with far-flung empires, were the real causes of this seismic cultural shift.

- argue:give reasons for or against sth, esp with the aim of persuading sb 说理; 争辩; 辩论: He argues convincingly. 他的辩解很有说服力. * argue for the right to strike 为争取罢工权利而辩论 * I argued that we needed a larger office. 我据理力争我们需要大些的办公室.

- far-flung:far away from where you are or from towns and cities

- seismic:原意是指“与地震有关的”,这里是比喻义:having a strong or widespread impact

- shift:change of place, nature, form, etc (位置﹑ 性质﹑ 形式等的)改变, 转变: a gradual shift of people from the country to the town 人们由乡村向市镇的逐渐转移 * shifts in public opinion 公众舆论的转变 * There has been a shift in fashion from formal to more informal dress. 服装的式样已经有了转变, 以前很拘谨现在较随便.

The European Renaissance remains one of the most important but misunderstood events in the history of western culture. The term “Renaissance” – referring to the revolution in cultural and artistic life that took place in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries – was first applied as late as the 19th century, when the French historian Jules Michelet used it in his History of France of 1855.

The European Renaissance remains one of the most important but misunderstood events in the history of western culture.

- remain:continue to be; stay in the same condition 仍然是; 保持不变: remain standing, seated, etc 一直站着﹑ 坐着等 * He remained silent. 他保持沉默. * Let things remain as they are. 一切保持现状吧. * In spite of their quarrel, they remained the best of friends. 他们尽管吵过架, 却仍不失为最好的朋友.

The term “Renaissance” – referring to the revolution in cultural and artistic life that took place in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries – was first applied as late as the 19th century, when the French historian Jules Michelet used it in his History of France of 1855.

- Renaissance:re- again;-nais ...: born | renaissance: rebirth

- was first applied 是跟在 The term "Renaissance" 后面的 apply:使用,采用 use

- Jules Michelet: 法国历史学家 wiki介绍

The Renaissance “… went from Columbus to Copernicus, from Copernicus to Galileo, from the discovery of the earth to that of the heavens. Man re-found himself”, according to Michelet. For him the voyage of Columbus in the 15th century, and the scientific achievements of Copernicus and Galileo in the 16th, defined a decisive shift from the narrow, religious world of the Middle Ages, and anticipated the modern world of science, technology and rationalism.

The Renaissance “… went from Columbus to Copernicus, from Copernicus to Galileo, from the discovery of the earth to that of the heavens. Man re-found himself”, according to Michelet.

- Columbus:哥伦布 wiki介绍 。哥伦布于1492年登上美洲大陆。

- Copernicus:哥白尼 wiki介绍。1543年,发表《天体运行论》,提倡日心说。

- Galileo:伽利略 wiki介绍:现代观测天文学之父、现代物理学之父、现代科学之父。1642年去世。

- from the discovery of the earth to that of the heavens:这一句中的that指的就是discovery。这一句很有意思,discovery of earth指的是发现新大陆,而discovery of heavens指的是对宇宙有了新的认识。

For him the voyage of Columbus in the 15th century, and the scientific achievements of Copernicus and Galileo in the 16th, defined a decisive shift from the narrow, religious world of the Middle Ages, and anticipated the modern world of science, technology and rationalism.

- 整句主体 the voyage defined ... and anticipated ...

- decisive shift: 决定性转变

- the Middle Ages: 中世纪(5th to 15th century) wiki介绍

- anticipate:预期、预见到将会发生

- rationalism:practice of testing all religious belief and knowledge by reason and logic 理性主义

Michelet’s invention of the Renaissance was refined and established by the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, in his book The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860). For Burckhardt, the Renaissance was a specifically Italian phenomenon, nurtures in the city-states of the 15th century, where the artistic talents of the likes of Leonardo, Botticelli, Mantegna and Brunelleschi flourished.

Michelet’s invention of the Renaissance was refined and established by the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, in his book The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860).

- refine:improve

- establish: cause people to accept (a belief, custom, claim, etc) 使人接受(信仰﹑ 风俗﹑ 要求等): Established practices are difficult to change. 积习难改. * His second novel established his fame as a writer. 他的第二部小说确立了他作家之名.

- Jacob Burckhardt:雅各·布克哈特 瑞士历史学家

For Burckhardt, the Renaissance was a specifically Italian phenomenon, nurtured in the city-states of the 15th century, where the artistic talents of the likes of Leonardo, Botticelli, Mantegna and Brunelleschi flourished.

- specifically:① relating to or intended for one particular type of person or thing only:advertising that specifically targets children | ② in a detailed or exact way:I specifically asked you not to do that!

- Italian phenomenon:意大利的现象。布克哈特对于文艺复兴的认识主要集中在意大利的种种文化以及政治经济改变中。

- nurture:(a) encourage the growth of (sth); nourish 培育, 培养(某物); 滋养: nurture delicate plants 培育幼嫩的植物. (b) (fig 比喻) help the development of (sth); support 扶植(某物); 支持: We want to nurture the new project, not destroy it. 我们要支持这个新工程, 不要破坏它.

- city-state:城邦

- talent:people who have this 有才能的人; 天才; 人才: We're always looking for new/fresh talent. 我们总是不断寻找新的天才. * an exhibition of local talent, eg of works by local amateur artists 当地人才作品展(如当地业余艺术家的作品展)

- the likes of: (infml 口) a similar person or thing 类似的人或物: He's a bit of a snob won't speak to the likes of me. 他这个人有点势利--不会和我这样的人说话.

- Leonardo:列奥纳多·达·芬奇 wiki介绍

- Botticelli:桑德罗·波提切利 wiki介绍 意大利艺术家

- Mantegna:安德烈亚·曼特尼亚 意大利插图画家 wiki介绍

- Brunelleschi:菲利波·布鲁内莱斯基 意大利建筑师、工程师 wiki介绍

Like Michelet, Burckhardt believed that the cultural achievements of the period heralded a “rebirth” of the classical Greek and Roman values of literary purity and aesthetic beauty. Both these historians believed that the Renaissance represented a questioning of religious authority, and a new spirit of artistic experimentation and scientific curiosity, which would ultimately give birth to modern, secular man.

Like Michelet, Burckhardt believed that the cultural achievements of the period heralded a “rebirth” of the classical Greek and Roman values of literary purity and aesthetic beauty.

- herald:announce the approach of sb/sth 宣布某人[某事物]即将来临: This invention heralded (in) the age of the computer. 这项发明宣告了计算机时代的到来.

Both these historians believed that the Renaissance represented a questioning of religious authority, and a new spirit of artistic experimentation and scientific curiosity, which would ultimately give birth to modern, secular man.

- question:质疑 express or feel doubt about (sth) 对(某事物)表示或感到怀疑: Her sincerity has never been questioned. 她的诚意从未受到怀疑. * Do you question my right to read this? 你是否怀疑我无权看这份材料? * We must question the value of our link with the university. 我们要斟酌一下与这所大学联系有何价值. * I seriously question whether we ought to continue. 我真正怀疑我们是否应该继续下去.

- religious authority:在文艺复兴之前的中世纪,宗教占据至高无上的地位,是绝对的权威。在文艺复兴时代,这一点受到了质疑。

- give birth to:produce young 生孩子; 产仔: She gave birth (to a healthy baby) last night. 她昨天晚上生了(一个健康的婴儿). * (fig 比喻) Marx's ideas gave birth to communism. 马克思的思想孕育了共产主义.

- secular:not concerned with spiritual or religious affairs; worldly 现世的; 世俗的: secular education, art, music 世俗教育﹑ 艺术﹑ 音乐 * the secular power, ie the State contrasted with theChurch 政权(非教会之权).

Until very recently, this invention of the European Renaissance has remained a powerful and seductive myth, which has ignored much of what was truly revolutionary about this extraordinary period in European history. The problem with the approach of both Michelet and Burckhardt to the Renaissance is that it reflected their own 19th-century world, characterized by European imperialism, industrial expansion, the decline of the church, and a romantic vision of the role of the artist in society.

Until very recently, this invention of the European Renaissance has remained a powerful and seductive myth, which has ignored much of what was truly revolutionary about this extraordinary period in European history.

- invention:注意,在前文中也出现过invention一词。将European Renaissance说成是invention,发明,是因为这个欧洲文艺复兴的概念是由上面提到的两个历史学家所定义和界定的。这个概念本身就是发明出来的,使人们对其的认识就集中在人类重新找回自己的这一主题上,并且将目光聚焦在了意大利。

- seductive: tending to seduce, charm or tempt sb; attractive 诱人的; 有魅力的; 有吸引力的: a seductive woman, smile, look 有魅力的女子﹑ 微笑﹑ 样子 * This offer of a high salary and a free house is very seductive. 这种高薪加免费住房的条件十分诱人.

- myth:神话、传奇、虚构的事情。本文的标题也用了myth一词。这充分体现了现代人所见到的都是对真实历史的演绎。对于文艺复兴的总体认识,我们可能一上来就想到各种名画,复古,伟大的艺术家等等,但这些也是19世纪的人们对于15/16世纪的历史的演绎罢了。

The problem with the approach of both Michelet and Burckhardt to the Renaissance is that it reflected their own 19th-century world, characterized by European imperialism, industrial expansion, the decline of the church, and a romantic vision of the role of the artist in society.

- approach:处理的方式、方法

- European imperialism:欧洲帝国主义

- industrial expansion:工业扩张

- vision:~ of sth (rhet 修辞) person or sight of unusualbeauty 异常漂亮的人或景象: She was a vision of loveliness.她是个可爱的美人儿

- 前面提到的两位历史学家受到了自己时代的局限,下文就讲到了这些局限是在哪里。

Neither of these writers explored how trade, finance, science and exchange with other cultures decisively shaped what they saw as the cultural flowering of the European Renaissance. Only now, in our more complex and interdependent global world, has it become possible to piece together a much more complex and dynamic picture of what really drove the cultural accomplishments of this remarkable period.

Neither of these writers explored how trade, finance, science and exchange with other cultures decisively shaped what they saw as the cultural flowering of the European Renaissance.

- shape:have a great influence upon (sb/sth); determine the nature of (sth) 对(某人[某事物])有重大影响; 决定(某事物)的性质: These events helped to shape her future career. 这些事促成了她後来从事的事业. * His attitudes were shaped partly by early experiences. 他的想法在一定程度上是由他早期的经历决定的.

- see sth. as ... 看作,视为

- the flowering of sth:[formal] when something develops in a very successful way: The nineteenth century saw a flowering of science and technology.

Only now, in our more complex and interdependent global world, has it become possible to piece together a much more complex and dynamic picture of what really drove the cultural accomplishments of this remarkable period.

- piece sth together (a) assemble sth from individual pieces 拼合﹑ 凑合或组装某物: piece together a jigsaw 装配好线锯 * piece together the torn scraps of paper in order to read what was written 把破碎的文件拼凑起来以阅读其内容. (b) discover (a story, facts, etc) from separate pieces of evidence 从各种证据中发现(事情原委﹑ 事实等): We managed to piece together the truth from several sketchy accounts. 我们从几方面粗略的说法中设法弄清了真相.

- picture: the general situation in a place, organization

- drive: 驱动、推动

What underpinned all the great artistic, literary and architectural achievements that we now see as quintessentially “Renaissance” was an equally momentous revolution in trade and finance. Ever since the Crusades of the 12th century, a politically fragmented and economically undeveloped Europe looked to the cultures of the east for luxury, wealth and new ways of doing business.

What underpinned all the great artistic, literary and architectural achievements that we now see as quintessentially “Renaissance” was an equally momentous revolution in trade and finance.

- underpin:(fig 比喻) form the basis for (an argument, a claim, etc); strengthen 为(论据﹑ 主张等)打下基础; 加强; 巩固: The evidence underpinning his case was sound. 有利於他的证据是确凿的. * These developments are underpinned by solid progress in heavy industry. 重工业的稳固发展为这些进展打下了基础.

- quintessentially:typically

- equally:同样地,这里是讲艺术、文学和建筑方面的成就与商业和金融业的变革进行了比较,前者的成就有多伟大,后者的变革就有多么重要。

- momentous:very important; serious 极重要的; 严重的: a momentous decision, occasion, event 重要的决定﹑ 场合﹑ 事件 * momentous changes 重大的变化.

Ever since the Crusades of the 12th century, a politically fragmented and economically undeveloped Europe looked to the cultures of the east for luxury, wealth and new ways of doing business.

- Crusades:十字军东征

- fragmented:四分五裂的 | fragment: v. to break something, or be broken into a lot of small separate parts - used to show disapproval

- look to: to depend on someone to provide help, advice etc 在我国西学东渐之前,原来西方也有“东学西渐”的时候

Early European maps show North Africa and what we would today call the Middle East at the heart of the known world. This was where Spanish and Italian merchants travelled to purchase the luxury goods, like silk, spices and ceramics.

Early European maps show North Africa and what we would today call the Middle East at the heart of the known world.

- 早期欧洲地图将北非以及我们如今所称为中东的地方放在已知世界的中心位置。

This was where Spanish and Italian merchants travelled to purchase the luxury goods, like silk, spices and ceramics.

- This:指的是上一句中所说的这个区域:北非+中东

The bazaars of the east also taught European merchants new ways of doing business. As early as the very beginning of the 13th century, the Pisan merchant Leonardo Pisan was travelling and trading throughout the Arabic east, where he gained the ability to calculate profit and loss using Hindu-Arabic numerals.

The bazaars of the east also taught European merchants new ways of doing business.

- bazaar:a street of small shops (especially in Orient)

As early as the very beginning of the 13th century, the Pisan merchant Leonardo Pisan was travelling and trading throughout the Arabic east, where he gained the ability to calculate profit and loss using Hindu-Arabic numerals.

- as early as ... 早在……时候

- Pisan:比萨(意大利城市) (Pisa的变形);比萨、比萨的

- Leonardo Pisan: 比萨的列奥纳多,指的就是著名的数学家斐波那契斐波那契,他以研究斐波那契数列而闻名于世。以前只听说过斐波那契是鼎鼎大名的数学家,没想到还是个生意人,没想到你是这样的斐波那契!

- Hindu-Arabic numerals: 印度阿拉伯数字 wikipedia介绍

In his revolutionary book Liber abbaci (1202) he introduced Europe to the Arabic methods of subtraction, addition and multiplication, explaining how he was “marvelously instructed in the Arabic-Hindu numerals and calculation”, and how they helped him in his business. Other European merchants openly traded with Muslim, African and Hindu businessmen, regardless of religious and cultural difference.

In his revolutionary book Liber abbaci (1202) he introduced Europe to the Arabic methods of subtraction, addition and multiplication, explaining how he was “marvelously instructed in the Arabic-Hindu numerals and calculation”, and how they helped him in his business.

- Liber abbaci:《计算书》,斐波那契的名著

- subtraction, addition and multiplication 减法、加法还有乘法

- instruct: 教导、指导

Other European merchants openly traded with Muslim, African and Hindu businessmen, regardless of religious and cultural difference.

- openly: 公然。如果想一下,文艺复兴是跟在黑暗的中世纪之后的,就明白此处为什么要用openly了

Europeans also learned the commercial usefulness of algebra from the Persian astronomer al-knowarizmi, and adopted the word “cheque” from the Arabic “sakk”. International finance became increasingly liquid and intricate during the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, and Florentine merchants based in the Medici bank opened offices throughout the east from the early 15th century onwards. They used “bills of exchange”, forerunners of the modern cheque, to secure lucrative contracts with Muslim merchants, who possessed the luxury objects desired by the elite of 15th-century Italy.

Europeans also learned the commercial usefulness of algebra from the Persian astronomer al-knowarizmi, and adopted the word “cheque” from the Arabic “sakk”.

- commercial usefullness of algebra: 代数的商业用武之地

- Persian:波斯的(现中东国家:伊朗)

- astronomer:天文学家

- al-knowarizmi:花拉子米 (wiki介绍在这里:花拉子米) 波斯数学家、天文学家,著有《代数学》

- 阿拉伯语中的“sakk”的意思是在合同契约上留下印记

International finance became increasingly liquid and intricate during the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, and Florentine merchants based in the Medici bank opened offices throughout the east from the early 15th century onwards.

- liquid:(finance 财) easily converted into cash 易转换成现款的: one's liquid assets 流动资产

- intricate:made up of many small parts put together in a complex way, and therefore difficult to follow or understand 错综复杂的: an intricate piece of machinery 一部复杂的机器 *a novel with an intricate plot 情节错综复杂的小说 *the intricate windings of a labyrinth 迷宫中扑朔迷离的路线 * an intricate design, pattern, etc 复杂的设计、图案等.

- Florentine: 意大利佛罗伦萨的

- Medici bank:美第奇银行(wiki介绍在这里:美第奇银行)

- from ... onwards ... 从……以后

They used “bills of exchange”, forerunners of the modern cheque, to secure lucrative contracts with Muslim merchants, who possessed the luxury objects desired by the elite of 15th-century Italy.

- bill of exchange: 汇票、票据

- forerunner:person or thing that prepares the way for the coming of sb or sth else more important; sign of what is to follow 先驱者; 开路人; 先兆: the forerunners of the modern diesel engine 现代柴油机的前身.

- secure:obtain sth, sometimes with difficulty 得到某事物(有时有困难): We'll need to secure a bank loan. 我们需获银行贷款. * They've secured government backing (for the project). 他们得到政府(对该计画)的支持.

- lucrative:producing much money; profitable 赚钱的; 可获利的: a lucrative business 赚钱的买卖

- luxury object:奢侈品

- elite:精英、名流

The result of this increasingly international trade revolutionized taste in Europe. The impact was felt on the art and culture of the 15th century. Religious and political commissions for altarpieces, frescoes and portraits of the rich and the powerful would often stipulate the amounts of expensive raw materials from the east that artists had to use to increase the opulence and grandeur of their creations.

The result of this increasingly international trade revolutionized taste in Europe.

- revolutionized: changed completely and abruptly

The impact was felt on the art and culture of the 15th century.

- the impact was felt on ...

Religious and political commissions for altarpieces, frescoes and portraits of the rich and the powerful would often stipulate the amounts of expensive raw materials from the east that artists had to use to increase the opulence and grandeur of their creations.

- commission: payment to sb for selling goods which increases with the quantity of goods sold 佣金; 回扣; 酬劳金: You get (a) 10% commission on everything you sell. 你可从售出的每种货物中得到10%佣金. * earn 2000 (in) commission 挣得2000英镑酬劳金 * She is working for us on commission, ie is not paid a salary. 她按挣回扣方式为我们工作(没有薪水).

- altarpiece: a painting or sculpture behind an altar 祭坛的装饰品

- fresco:湿壁画

- stipulate:state (sth) clearly and firmly as a requirement 讲明, 规定(某要求): I stipulated red paint, not black. 我已讲明要红漆, 不要黑漆. * It was stipulated that the goods should be delivered within three days. 按规定货物须在三日内送交.

- raw materials: 原材料

- opulence:richness, luxuriousness

- grandeur: greatness; magnificence; impressiveness

- 可见,那些伟大的作品,不尽其艺术性价值非常高,如果考虑用的原材料,也是价值很高的

Patrons drew up contracts with artists that specified the exact amounts of gold and silver to be used in the painting. For many people, the splendor of the painting was reflected by the sheer amount of material expense lavished on its creation.

Patrons drew up contracts with artists that specified the exact amounts of gold and silver to be used in the painting.

- patron:person who gives money or other support to a person, cause, activity, etc 资助人; 赞助人: a wealthy patron of the arts 艺术方面的富有的赞助人.

- draw up contract: 签订合同

- specify:明确标明

For many people, the splendor of the painting was reflected by the sheer amount of material expense lavished on its creation.

- sheer: complete; thorough; utter 完全的; 彻底的; 十足的: sheer nonsense 一派胡言 * a sheer waste of time 纯粹浪费时间 * by sheer chance 完全出於偶然地.

- lavish sth on/upon sb/sth give sth to sb/sth abundantly and generously 慷慨而大量地给某人[某事物]: lavish care on an only child 对独生子女关怀备至.

- 对许多人而言,画作的光彩完全体现在创作它洒了多少钱在原料上。

Some Italian city-states laid claim to political preeminence through the commissioning of hugely ambitious works of art. In Florence, the commercial power of the Medici family bankrolled Brunelleschi’s dome (1437), Donatello’s statue David (c. 1420s), and Benozzo Gozzoli’s extraordinary frescoes depicting the Adoration of the Magi (1459), which adorned the walls of the Medici Palace. As well as triumphant artistic achievements, these creations all celebrated the political and financial power of the family that had commissioned them: the Medici.

Some Italian city-states laid claim to political preeminence through the commissioning of hugely ambitious works of art.

- city-state:城邦

- lay claim to: 要求、自认为、宣称有

- preeminence:卓越, 杰出

In Florence, the commercial power of the Medici family bankrolled Brunelleschi’s dome (1437), Donatello’s statue David (c. 1420s), and Benozzo Gozzoli’s extraordinary frescoes depicting the Adoration of the Magi (1459), which adorned the walls of the Medici Palace.

- Medici family:美第奇家族(维基介绍在这里:美第奇家族)

- bankroll:to provide the money that someone needs for a business, a plan etc

- Brunelleschi’s dome:Brunelleschi这位建筑师之前提到过。1418年佛罗伦萨市政府公开征集能够设计并建造大圆顶的方案。精通罗马古建筑的工匠菲利波·布鲁内列斯基胜出,为总建筑师。在建造拱顶时,没有采用当时流行的“拱鹰架”圆拱木架,而是采用了新颖的“鱼刺式”的建造方式,从下往上逐次砌成。主教座堂于1436年3月25日,举行献堂典礼。百年之后,米开朗基罗在罗马圣彼得大教堂也建了一座类似的大圆顶,却自叹不如:“我可以建一个比它大的圆顶,却不可能比它的美。”

- Donatello’s statue David:多那太罗的雕塑:大卫。注意,不要与米开朗基罗的大卫混淆

- Benozzo Gozzoli’s extraordinary frescoes depicting the Adoration of the Magi

Adoration of the Magi是圣经中一个典故。只东方三智者追随着一颗星星找到了耶稣,并送上礼物。关于这一主题的艺术作品也有很多。 - adorn:装饰

- Medici Palace:美第奇宫(维基介绍在这里:美第奇宫)

As the flow of exotic goods from east and west reached the markets of northern Europe, Albrecht Durer was one among many artists recording his delight at “wonderful works of art, and I marveled at the subtle ingeniousness of people in foreign lands”. He snapped up porcelain, parrots, sandalwood and coconuts, many of which he incorporated into his drawings and paintings.

As the flow of exotic goods from east and west reached the markets of northern Europe, Albrecht Durer was one among many artists recording his delight at “wonderful works of art, and I marveled at the subtle ingeniousness of people in foreign lands”.

- flow of exotic goods: 异域货品的流动

- Albrecht Durer:阿尔布雷希特·丢勒(维基介绍看这:丢勒)

- record:记录了

- delight at:见到……的欣喜、高兴

- marvel:~ at sth (fml 文) be very surprised (and often admiring) 大为惊讶(常含赞叹之意): marvel at sb's boldness 赞佩某人勇敢 * I marvelled at the maturity of such a young child/at the beauty of the landscape. 小小年纪如此成熟[风景之美]使我赞叹不已. * I marvel that she agreed to do something so dangerous. 我大为惊异的是, 她竟同意做如此危险的事.

- subtle:难以形容的、精细的、精巧的

- ingenious:1. an ingenious plan, idea, or object works well and is the result of clever thinking and new ideas 2. someone who is ingenious is very good at inventing things or at thinking of new ideas

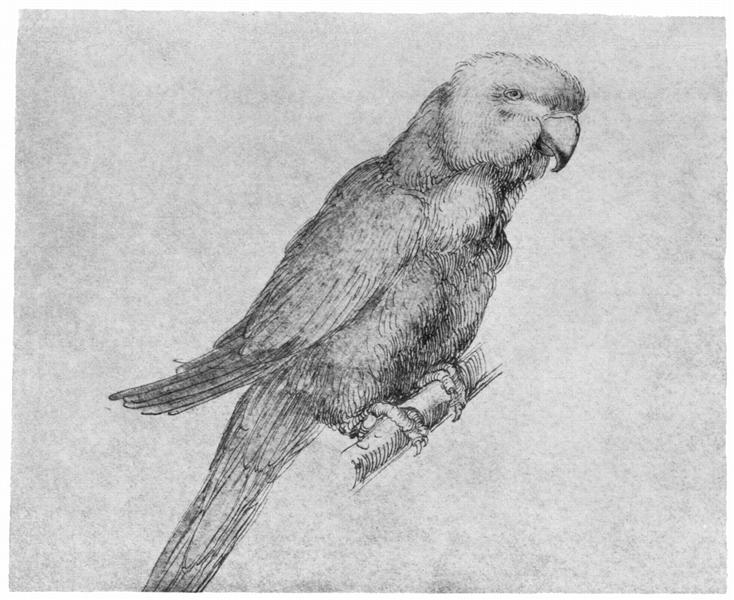

He snapped up porcelain, parrots, sandalwood and coconuts, many of which he incorporated into his drawings and paintings.

- snap sth. up: buy or seize sth quickly and eagerly 抢购或迅速抓取某物: The cheapest articles at the sale were quickly snapped up. 大减价货物中最便宜的物品很快抢购一空. | 这里形容丢勒很乐意在画作中表现这些来自异域的东西。下面这幅就是丢勒画的鹦鹉

- sandalwood:檀香

- incorporate: ~ sth (in/into sth) make sth part of a whole; include 将某事物包括进去; 包含: Many of your suggestions have been incorporated in the new plan. 你的建议多已纳入新计画中.

Just like Mantegna, Brunelleschi and Leonardo before him, Durer was a worldly and inquisitive artist, who was intimately connected to the latest developments in trade, politics and science – and this is exactly what gives Renaissance art its vivid originality and technical brilliance. What we’re left with is a vision of the Renaissance as a much dirtier, more worldly place than Michelet and Burckhardt believed, but this only adds to its singular importance in the history of western cultural life.

Just like Mantegna, Brunelleschi and Leonardo before him, Durer was a worldly and inquisitive artist, who was intimately connected to the latest developments in trade, politics and science – and this is exactly what gives Renaissance art its vivid originality and technical brilliance.

- worldly: practical and having a lot of experience of life: She seems to be much more worldly than the other students in her class.

- inquisitive: interested in a lot of different things and wanting to find out more about them 这里inquisitive是用作褒义的。但是inquisitive在不同场合下,也常常用作贬义,表示“好打听事情的”

- originality:when something is completely new and different from anything that anyone has thought of before

- brilliance: very high level of intelligence or skill

What we’re left with is a vision of the Renaissance as a much dirtier, more worldly place than Michelet and Burckhardt believed, but this only adds to its singular importance in the history of western cultural life.

- What we're left with ... 剩下给我们的就是…… 这里说的是前面讲了那么多,说明文艺复兴不仅仅是关乎艺术方面,更是关于商业、科技等等。所以现在给我们留下的文艺复兴的印象就是……

- a vision of ...: ……的景象

- a much dirtier, more wordly place: 这里的dirtier并不针对只更肮脏,而是只并不是向Michelet和Burckhardt讲的那么单纯,那么阳春白雪,而是更加世俗的、接地气的

- add to its importance: 增添了其重要性

- singular: outstanding; remarkable 突出的; 非凡的: a person of singular courage and honesty 极为勇敢和诚实的人.